by Steve Schwinghamer, Historian

(Updated January 28, 2022)

Canadian immigration history can be researched using a staggering variety of sources. There are ship logs and passenger manifests, architectural plans and harbour maps, photographs and paintings, letters and telegrams, tweets and emails, laws and policies, diaries and memoirs, oral histories and digital stories, items brought from the old country, objects acquired in the new home, media reports of all kinds, films and lantern slides…the range is humbling.

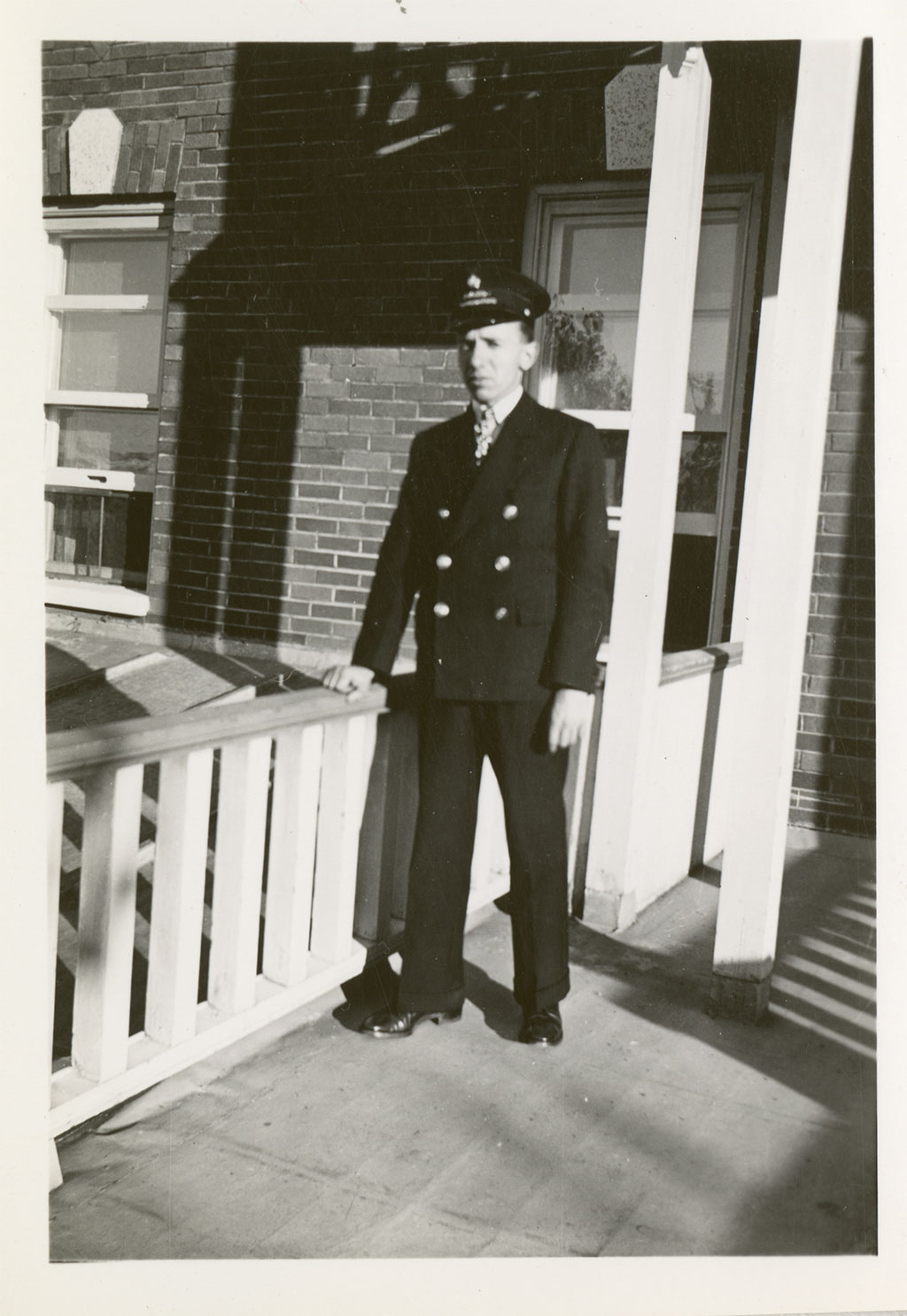

Each resource has strengths and limitations for historians. One of the challenges of the official records produced by immigration officials generally is that they are “dry,” and, particularly at the local level and for lower-level officials, there are limited opportunities for the officials to introduce personal responses or reflections in their record-keeping. Nevertheless, these government records establish the political, cultural, and physical contexts for immigrant reception, as well as reflecting immigrants’ responses to official interventions.[1] In some cases, more personal reflections in these files (such as confidential letters, personal notes, or internal memos) dramatically expand our insight into the attitude and approach of specific individuals. One of these individuals is Fenton Crosman, whose career with the Canadian immigration department spanned from the 1930s to the 1960s, at posts all over central and eastern Canada.

Credit: Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 Collection (D2014.357.5)

Gaining insight into the personal positions of the officers and agents working in Canadian immigration can help decode some of the carefully-worded official documents, where the culture of the department generally promoted efforts to fog over and conceal potentially controversial policies or practices. For instance, the Continuous Journey Regulation was described and defended in public as a regulatory requirement to preserve the ability of the department to refuse immigrants that came to Canada by a route that would complicate later deportation (if necessary). Private instructions issued to immigration agents on behalf of the Superintendent of Immigration, however, stated that while the regulation was “absolutely prohibitive in its terms,” it was only meant to be used against “really undesirable immigrants.”[2] This private instruction significantly modifies our understanding of the use of policy and discretion: the department intended selective, discriminatory enforcement of what appeared to be a stringent policy. The internal dialogue also shows the long historical trajectory of bureaucratic influence on Canadian immigration policy.[3]

These personal resources are transformative tools for approaching the history of the Canadian immigration department. So much relied on—and was intended to rely on—secret or coded practices of inclusion and exclusion enacted by individuals that are not based on plain-language regulations. Personal resources also help break down the risky perception of Canada’s border and immigration authorities as monolithic, both by emphasizing this discretion but also giving us evidence of divergence and of individual influence.

Credit: Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 Collection (D2013.1912.62)

In this vein, one of the most interesting and varied personal sources from an immigration officer that I have encountered is Fenton Crosman’s edited and expanded diary, published by the Canadian Immigration Historical Society.[4] Crosman himself alludes to the relationship between government documents and the personal in his introduction: “There is more to immigration than rules, regulations and procedures. Immigration means human beings, and to deal with these human resources I found at Saint John a staff…as interesting and varied as the newcomers passing through their hands.”[5] Crosman’s insights are not limited to the principal offices, as his earlier career saw no few days at quiet border points. Crosman includes sketches of colleagues throughout the immigration system, including a few of Customs agents who filled the role of immigration officers in minor ports.

Along the way I have been calling on the Collectors of Customs, who are also part-time Immigration Officers, at the small Ports in Northern New Brunswick. I shall mention two in particular. During the work at head office, I have read many reports from Mr G., many of them written in a dry, humorous vein, and I was eager to meet the man. He is hardly the type I expected to see. He is middle aged, with deep-set serious eyes, and in his spare time is a gentleman farmer, chess player and a poet. He showed me a collection of his verses, many of which appear to be quite good. His office records, however, are a complete mess, and this includes, of course, our Immigration records. Mr G. admits, himself, that he is a poor office man, and that his own Department is always criticizing him about this. I’m afraid that nothing can be done about it and, as he is a most sincere soul, and so far has done our work satisfactorily, I shall make the best report possible.

In contrast, there is Mr. M. He is a young man; his office is 100% ship-shape: and he is keen as a new blade when it comes to asking questions about our work. He wants to see things done efficiently and, like some of the officers at the other small ports, is particularly concerned about sick mariners left in hospital, what to do with them when they have been released, what to do when the ship’s agents refuse further responsibility and when our Department, true to policy, refuses to take any money out of the cash deposit made when the mariner was left behind.

Mr. M. has made several useful suggestions. He would make an excellent Immigration officer, instead of working for the Customs.[6]

Crosman also provides a window into the culture of the civil service that he joined, with one of my favourite entries being his comments about French testing:

To the Dept. at nine o’clock and, after they had finished describing the likelihood of my being carried out in an ambulance, a hearse, or other vehicle, they told me that I was to report this a.m. at the C.S. Commission for an oral examination in French. Well, I went there in fear and trembling, but there met a kind gentleman, who asked me various questions in French concerning our work, and then had me write about a dozen sentences. Although his questions were rapid, I had no difficulty in answering them, and he appeared to be quite satisfied with my efforts.

At the office they stoutly denied that anyone has objected to my appointment [as a temporary Inspector-in-Charge at Huntingdon, QC], but someone tells me that powerful forces are at work to have the position filled by either a French-Canadian or a Roman Catholic, according to tradition. Well! I might have expected that. It is an interesting situation.[7]

This kind of contextual backdrop helps illuminate some of the internal frictions in the department, as well as providing a contemporary support for interpretations of the forms of patronage and regional practices that are often visible but difficult to substantiate through materials like the civil service list. The office teasing and the tensions over bilingualism probably resonate in many modern Canadian federal workplaces, and—as Chilton and Takai argue—pulling back the veil from political machinations is valuable. However, a critical contribution of a memoir like Crosman’s is some access to the nuance of daily work in immigration. Crosman does delve into some particulars of decision-making and where discretion intersected with regulation or policy. For instance, in April of 1939, Crosman was confronted with a person who seemed admissible but provoked suspicion:

We made another man unhappy today by refusing his entry to Canada. He is a refugee from Hungary, on his way to New Zealand, who wanted to stop over in Canada for about two months and to visit his brother in the United States. All seemed well until he produced an address book which included the name and address of a well-known shyster New York lawyer famous for assisting the illegal entry of aliens to Canada and the States. Our man, however, pretends absolute innocence, insisting that this name and address was given to him by a man whom he met at a dinner in London, and that he had no previous acquaintance with either his dinner companion or the lawyer. His story, on the whole, seems good, but we are sufficiently doubtful to refer it to the Department.[8]

Under the restrictive immigration regulations of the 1930s, this error in favour of detaining and investigating the man is not surprising. The implications of the text, though—that officers checked address books, that they would recognize lawyers involved in shady cases, and so on—underscores the kind of scrutiny that even a person claiming entry only as a visitor might endure at the time. This goes to the atmosphere of suspicion (and some actual attempts at subterfuge) surrounding migrations broadly just before the Second World War. The officers were obviously aware of the (still common) practice of overstaying a visa as a method of illegal entry into a country. For context in time, this rigorous check and detention of a potential visitor happened just weeks before MS St. Louis sailed from Germany.

Credit: Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 Collection (D2013.1912.1)

This indirect or inverted access to the experience of immigrants is valuable too because there are no systematic records of the process created from the other side of the immigration desk, representing the perspective of people seeking entry into Canada. Crosman is selective in his representation, but the examples he chooses are nevertheless illuminating. Given the work of the department, this contact sometimes extended for years after arrival, as immigrants settled and then sought to sponsor relatives. Crosman offered an amusing and enthusiastic report in March of 1939, writing:

Left Ottawa this morning and, having arrived at Joliette, P.Q., I registered at a hotel and arranged to set forth into the country to do my assignments. They brought along a horse and rig, expecting me to go alone. But I don’t belong to the horsey set and don’t yet wish to commit suicide, so persuaded the driver to come with me…

Most inspiring visit of all was at the farm of a middle-aged Slovak couple, who came out here only a few years ago. Now they want to bring some relatives. True, they haven’t much property or money, but make the most of what they have. There was evidence of thrift everywhere and, in all his eagerness to show me his accomplishments, the old man forgot all about his rheumatism and climbed around the barn faster than I could follow him.[9]

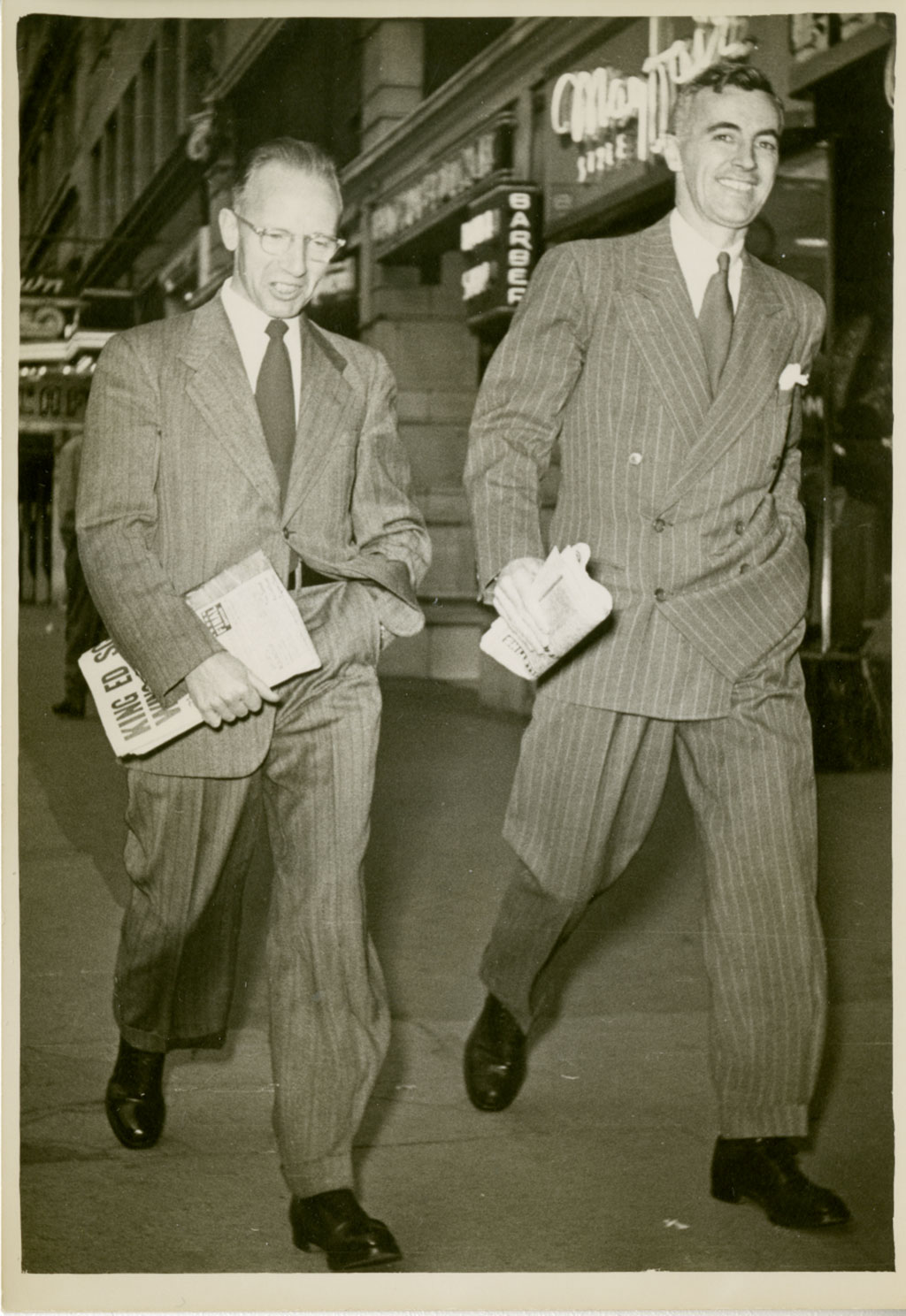

Crosman’s writing ranges quite a bit in scope, transitioning from the personal to the interactions of US and Canadian immigration policies at our borders. The personnel of the two country’s immigration departments worked closely, and often were stationed at major ports in the other country (Canadians at New York; Americans at Quebec or Vancouver, for instance). Canadians often looked to American implementations of screening or (sometimes dubious) expertise to cement approaches to our own regulatory problems. Even the design of our immigration facilities sometimes made reference to American examples.[10] Such close cooperation, however, did not guarantee smooth functioning, and Crosman owns an error related to US practices in 1938.

Already I learn that I got stung on a case yesterday morning. The great difficulty for officers here is in connection with U.S. visas cases – aliens in the United States who come to Canada for a Consular visa, enabling them to qualify for permanent residence in the U.S.A. Instructions from the Department require special handling of these cases, for if lacking the proper documents the applicant may not be permitted to return to the States and may thus be stranded in Canada. In many instances where an alien cannot obtain the necessary documents to present to a U.S. Consul in Canada, he comes up to Montreal on a “visit”, denying the real purpose of his coming here. Such was the man I had on the train yesterday morning. He misrepresented his case to me, but fortunately returned this morning with his U.S. visa and was permitted to return there. However, the Department will not know of my error in judgement and I suppose the way to learn is by trial and error.

To the office this p.m. to see Charlie F., and have the boss call my attention to the mistake I made, even though all’s well that ends well.[11]

Credit: Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 Collection (D2013.1912.23)

Crosman’s memoir brings us access to the activities of the immigration department and its agents in a unique and valuable way. His journaling complements the official documentary records of process and regulation with an inside perspective, leavened by his dry, self-effacing wit. From colleagues to workplace culture, from enforcement to international cooperation, Crosman’s writing offers many avenues for insight into the historical immigration department. Although the journal is not overly personal, a few little notes sneak in: observations of a young woman he might like to spend more time with, the tumultuous and unsettled nature of work as a traveling inspector, and living with impaired mobility in one leg. These can bring a poignant humanity to the immigration functions that filled Crosman’s days.

This was a most harrowing day for me, for I’ve been before the Army Medical Board, as arranged by the Superintendent, so I’d finally know just where I stand in relation to the draft. Finally got through by 4:30 p.m., and all this for a Category “E” – an absolute rejection, due of course to my game leg. I felt like weeping over it, but they seemed glad at the office to have me stay on.

Oh, well, I can stay at home and pay the new taxes.[12]

It would be unfair to close without a look at the impish humour that animates the writing throughout. Crosman’s personality comes through the pages to such an extent that, with the permission of his family, the Canadian Museum of Immigration adopted his first name for our mascot bear. For staff of the Museum, the bear is accompanied by an elaborately-costumed stuffed flea, for reasons that I must leave to Crosman’s explanation:

When at Halifax to write my reports I occupied a desk in the noisy main office, where I had no privacy and nowhere to keep personal papers. The boss, however, kindly allowed me to share a filing cabinet in his private office, and it was there that I kept my pet flea, Igor, an imaginary character who was my alter ego or other personality, who dared to do forbidden deeds and to play tricks that any right-minded Methodist would quake to look upon. Nevertheless, all went well until Igor was accused of getting into the boss’s whiskey.[13]

Credit: Photo by Colin Timm

- Lisa Chilton and Yukari Takai, “East Coast, West Coast: Using Government Files to Study Immigration History,” Histoire Sociale/Social History, 48:96 (May 2015), 9-10.

- Library and Archives Canada, Department of Employment and Immigration fonds, RG 76, volume 481, file 745162 Private, “Private Instructions to Port agents. Emigrants prohibited from coming to Canada unless coming by a continuous journey from the country of their birth or citizenship,” Circular to Dominion Immigration Agents by L.M. Fortier for W.D. Scott, Superintendent of Immigration, 1 April 1908.

- For a study of this is more recent context, see Mireille Paquet, “Immigration, Bureaucracies and Policy Formulation: The Case of Quebec,” International Migration, February 2019.

- Fenton Crosman, Recollections of An Immigration Officer: The Memoirs of Fenton Crosman, 1930-1968, No. 2 in Perspectives on Canadian Immigration (Ottawa: CIHS, 1989). The title quote is from 21 October 1937, page 49.

- Crosman, 13.

- Crosman, 16 April 1941, 141-142.

- Crosman, 21 March 1940, 113-114.

- Crosman, 29 April 1939, 87.

- Crosman, 28 March 1939, 84.

- Patricia Roy, A White Man’s Province: British Columbia Politicians and Chinese and Japanese Immigrants, 1858-1914 (Vancouver: UBC Press, 1989), 57; LAC RG 76 File 142 Part 1; Report of Traveling Inspector J.M. Gordon to DM A.M. Burgess, Ottawa ON, 11 April 1894; Part 6 John Kennedy to W.D. Scott, Montreal QC, 10 May 1912. Collaboration at ports of entry was common and some major Canadian immigration facilities, including Pier 21, were developed with allocations for American processing in their design.

- Crosman, 1 March 1938, 57-58.

- Crosman, 24 June 1942, 167.

- Crosman, 190.