by Jan Raska, PhD, Historian

(Updated November 5, 2020)

In summer of 2012, I visited Library and Archives Canada in Ottawa to conduct archival research for the historical context component of our temporary exhibition Position As Desired / Exploring African Canadian Identity, featured from 22 January to 30 March 2013. I came across an old Immigration Branch record pertaining to an African Canadian woman named Rebecca Barnett. The microfilmed record was titled: “Rebecca Barnett – undesirable (insane) (Black).” I found this title odd, dated, and biased. Curious, and a bit taken aback, I proceeded to explore the content further. I subsequently came across a Department of Justice record titled “Deportation of Rebecca Grizzle (coloured), public charge in Toronto General Hospital.” In the former, I found a story that spanned immigration, citizenship and expatriation legislation, and heavily underlined the discriminatory racial/ethnic and gender understanding of the period spanning the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Including the latter case, I began to wonder what role identities – in this instance: African Canadian, women, mentally ill, public charge – played in their cases? With Rebecca Barnett, Canadian and American immigration authorities could not agree on her citizenship. As for Rebecca Grizzle, Canadian immigration officials were unsure of the legality of deporting a public charge who was to be financially supported by a private organization.

Women’s Rights after Confederation

First, we must explore what place and what rights women held in law during both Rebeccas’ lives. The British North America Act created the Dominion of Canada in 1867. This legislation used “he” and “persons” to refer to more than one individual. Women were left out. Under the law, they were not seen as persons. A British court ruling in 1876 dictated that Canadian women were “…persons in matters of pain and penalties, but are not persons in matters of rights and privileges.”[1] Women such as Rebecca Barnett and Rebecca Grizzle were not considered equal to men under the law.

The Case of Rebecca Barnett

Barnett was born in Chippewa, Ontario and spent close to twenty years there before heading to the United States. In 1884, she married Alfred S. Barnett from Omaha, Nebraska. Alfred later served as the head porter on the Pullman Railway dining car between Chicago, Illinois and Bay City, Michigan. The couple lived throughout the United States – never staying too long in one place.

When Barnett became afflicted with a mental illness, her husband sent her back to Canada for treatment. In 1886, Rebecca Barnett was admitted to the Asylum for the Insane in Hamilton, Ontario (hereafter Hamilton Asylum). Upon his wife’s admission, Alfred Barnett later obtained a divorce and remarried. Approximately two decades later, Rebecca Barnett remained a resident of the Hamilton Asylum. Unbeknownst to Rebecca, her hometown of Chippewa contacted provincial authorities to dispute why they continued to be charged for her care.

Canadian and American Officials Debate Barnett’s Citizenship and Residency Status

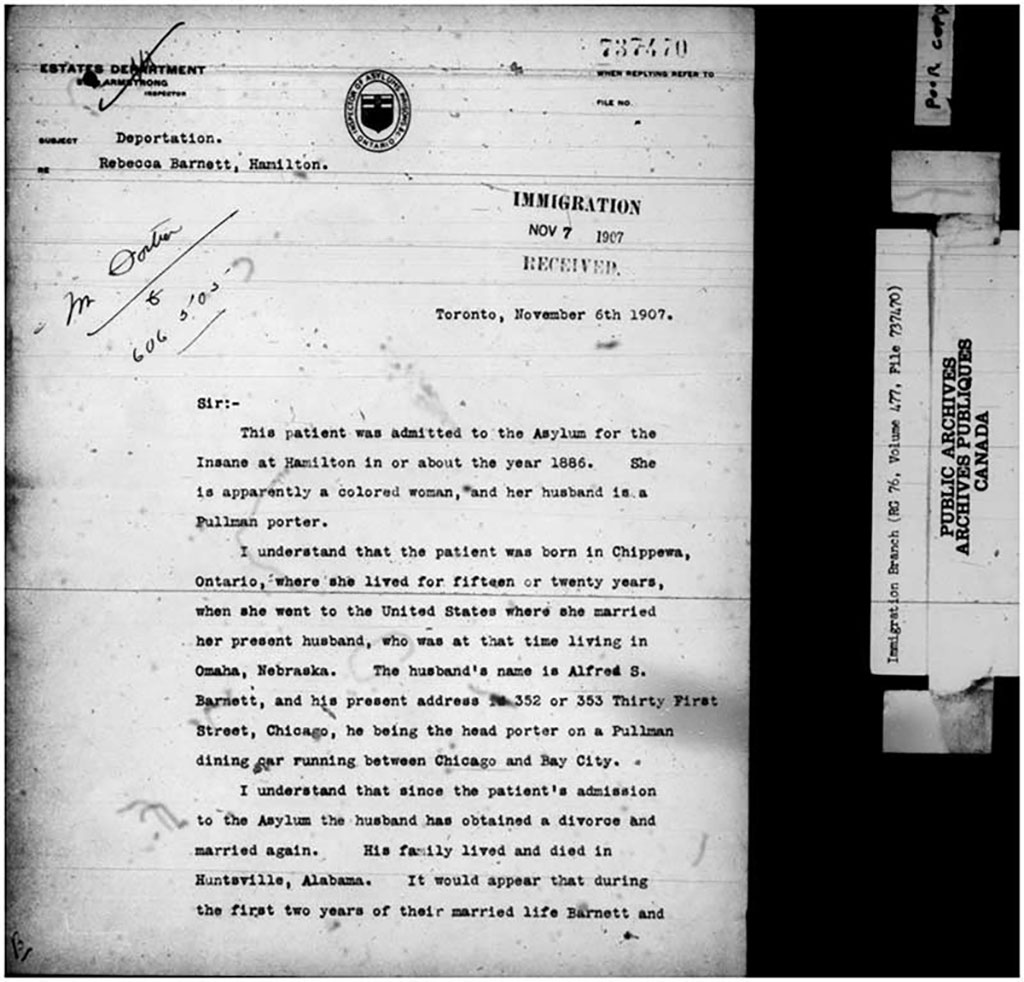

In a letter, dated 6 November 1907, from S.A. Armstrong, Ontario Inspector of Asylums, Prisons, and Public Charities to W.D. Scott, Superintendent of Immigration in Ottawa, Barnett’s residency was outlined:

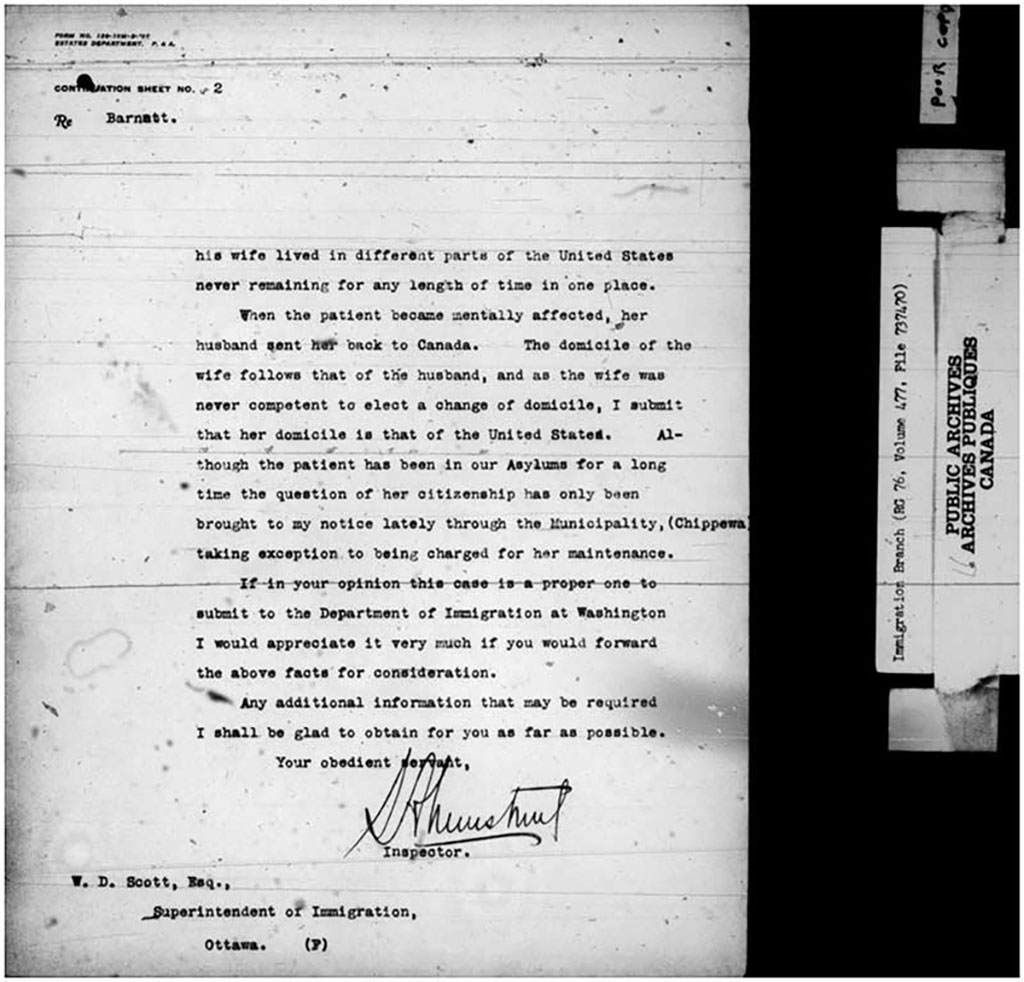

When the patient became mentally affected, her husband sent her back to Canada. The domicile of the wife follows that of the husband, and as the wife was never competent to elect a change of domicile…her domicile is that of the United States. Although the patient has been in our asylums for a long time the question of her citizenship has only been brought to notice lately through the Municipality, (Chippewa) taking exception to being charged for her maintenance.[2]

The Ontario Inspector wondered whether Barnett’s case should be referred to the United States Department of Immigration in Washington. Nine days later, E.J. Wallace, the Acting U.S. Commissioner of Immigration in Montreal informed Canadian immigration authorities that if Rebecca Barnett continued to reside in her country of birth, she “…could hardly be called a citizen of the United States” even with her American citizenship – conferred on her through her marriage to Alfred Barnett.[3]

American immigration authorities referred to “the uniform practice in the United States to hold that a woman partakes of the status of her husband so far as citizenship is concerned.” Regardless of Rebecca Barnett's status as a Canadian citizen by birth, her marriage to Alfred Barnett subsumed her birthright for an American citizenship. Wallace pointed out to his Canadian counterparts that while Rebecca Barnett’s case was “…certainly somewhat novel and peculiar,” she was not a citizen of Canada due to her marriage. In assuming that immigration legislation was not intended to be retroactive, the Immigration Act of 1906 would not apply to Barnett who returned to Canada prior to the introduction of the Act, and therefore could not be included within its provisions.[4]

However, American immigration authorities indicated that with the recent passage of the Expatriation Act in March 1907, a naturalized citizen who now resided for a period of two years in their country of origin would lose their American citizenship.[5] Rebecca Barnett spent over two decades in residence at the Hamilton Asylum prior to the passage of the Expropriation Act. In the eyes of American officials, Barnett was no longer considered an American citizen.

Canadian Officials Disagree with Their American Counterparts Regarding Barnett’s Citizenship

Disappointed with the American interpretation of the Barnett case, Ontario Inspector S.A. Armstrong informed Superintendent of Immigration in Ottawa, W.D. Scott, that the American response was “…entirely contrary to decided cases and to the rules of private international law generally.”[6] Armstrong focused his letter to Scott on two points: nationality and domicile. In attempting to ascertain whether Rebecca Barnett belonged to the province of Ontario or the United States, Armstrong argued that “…she should be maintained by the United States” because of her marriage to an American citizen. At the time, international law dictated that a woman acquired the nationality of her husband. Armstrong believed that the couple’s divorce in 1886 should not be factored into any decision on Rebecca Barnett's citizenship.[7]

In the case of domicile, the Ontario Inspector argued that since Alfred Barnett’s residence at the time of his marriage to Rebecca Barnett was in the United States, the wife’s domicile remained in the United States even after she was brought back to Canada for treatment. According to Armstrong, a voluntary change of domicile would have to occur for Rebecca Barnett’s status to change. Given her long term stay at the Hamilton Asylum, she may have been unable to understand and/or request such a change. Since Alfred Barnett returned home to the United States, Armstrong argued that Rebecca Barnett's residency status remained with him.[8]

Although American immigration authorities believed that Rebecca Barnett had lost her American nationality, Canadian legislation did not automatically reinstate her citizenship. As a result, she remained a statutory alien until either country deemed her to be a citizen.

Believing he could no longer deal with the case, W.D. Scott sought a judicial interpretation from W. Stuart Edwards, Acting Deputy Minister of Justice in Ottawa. Edwards replied that it was his belief that:

…any British subject is subject to loss of domicile for the purposes of the Act under the provisions of said section. If a native-born Canadian loses his domicile under said section, he does not cease to be a Canadian citizen, but I am of [the] opinion that if a woman being an alien becomes a British subject by virtue of her marriage to a Canadian-born citizen, and loses her domicile under said section whether before or after the termination of the marital relation, she ceases to be a Canadian citizen…[9]

The Acting Deputy Minister of Justice agreed with the Ontario Inspector that while Rebecca Barnett was born in Canada and remained a mentally ill patient of the Hamilton Asylum, she was no longer a Canadian citizen.

The Case of Rebecca Grizzle

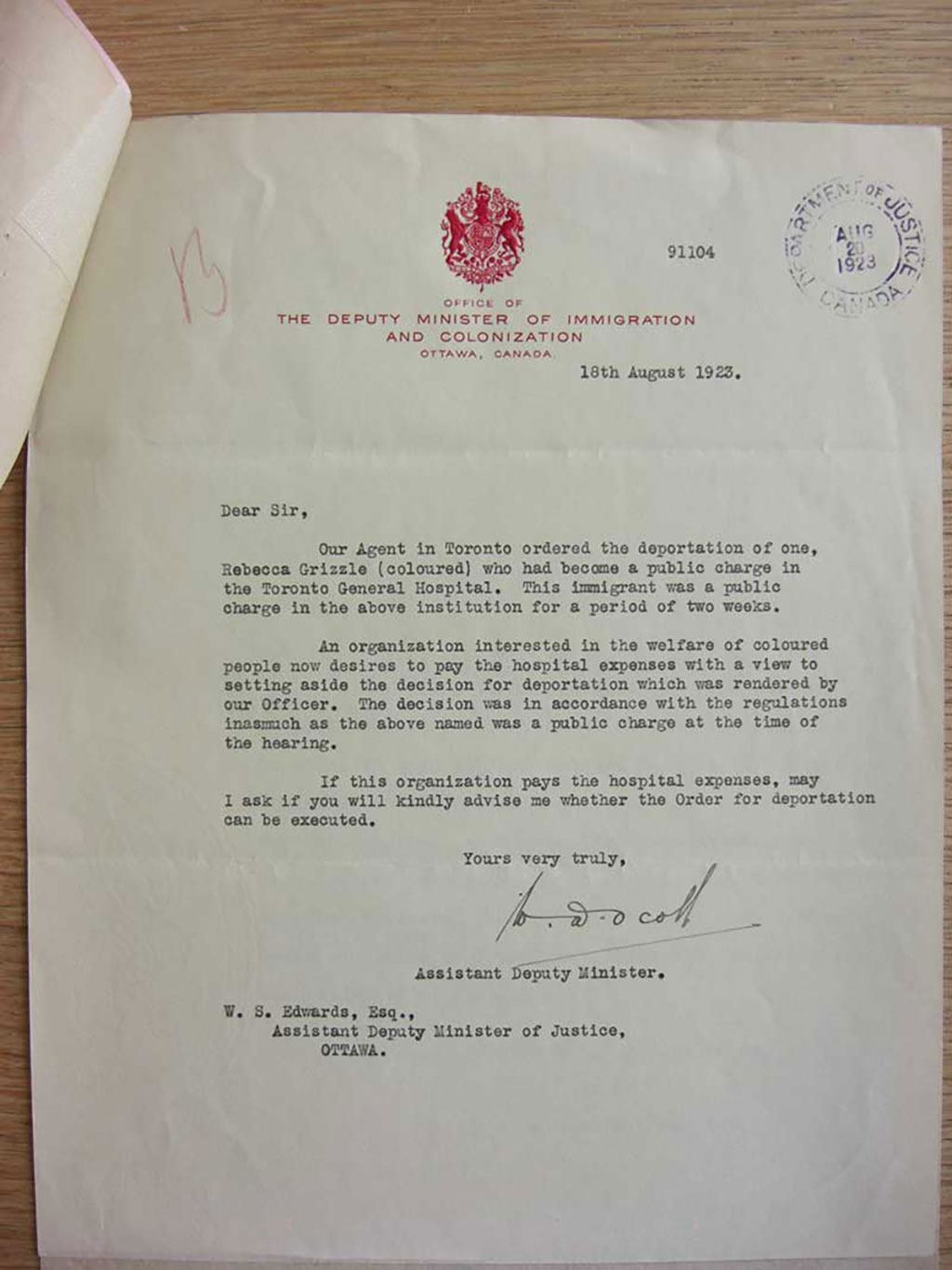

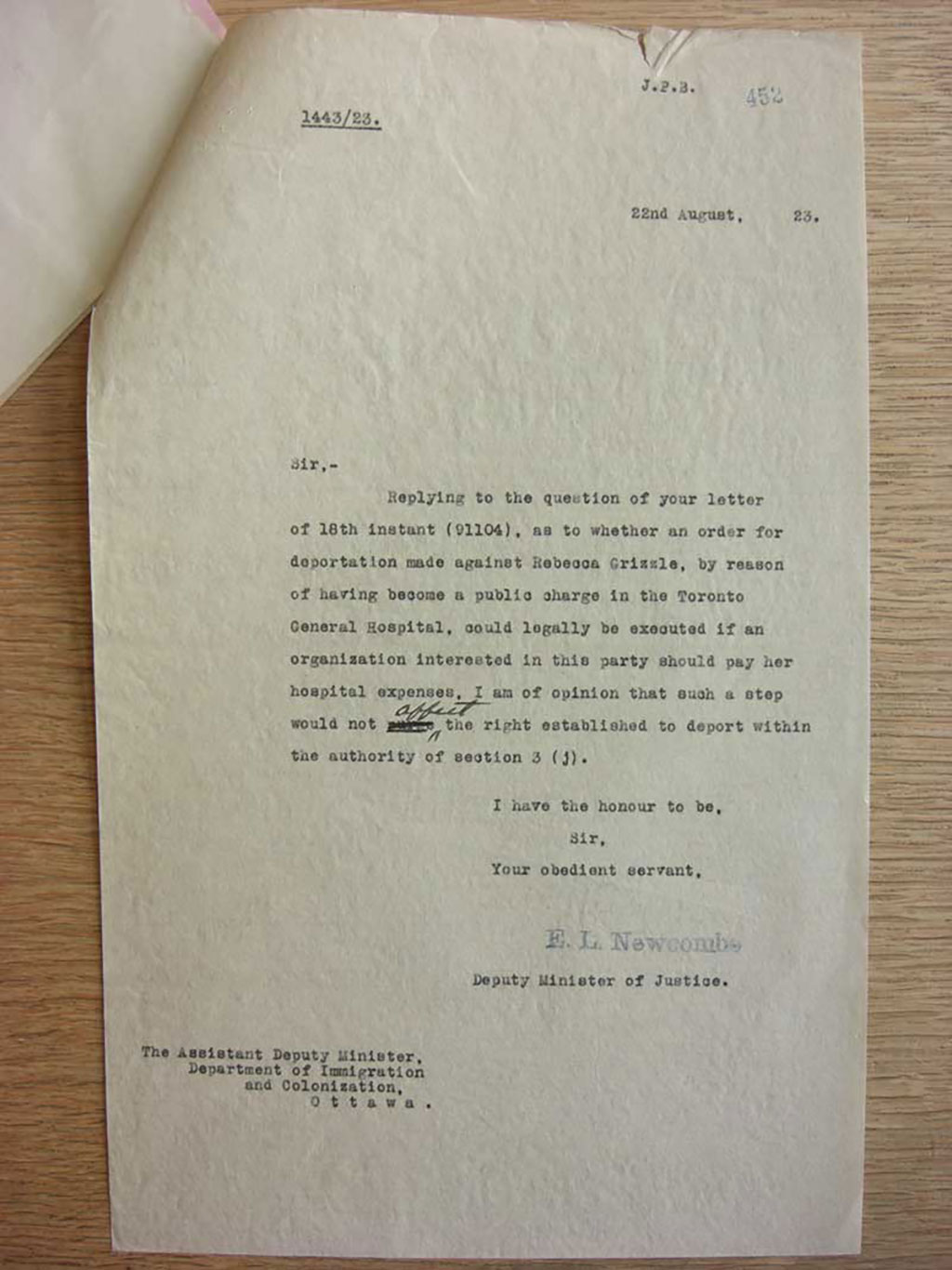

In 1923, a Canadian Immigration officer in Toronto sought the deportation of Rebecca Grizzle, an African Canadian woman hospitalized at the Toronto General Hospital. Although not much is known of her, Rebecca Grizzle was hospitalized for a period of two weeks. For her stay there in the hospital, Grizzle was deemed a public charge for not paying her medical bill, and subject to deportation by federal officials. On 18 August 1923, the Deputy Minister of Immigration and Colonization wrote to W. Stuart Edwards, Assistant Deputy Minister of Justice to inform him that an unknown organization “interested in the welfare of coloured people now desires to pay the hospital expenses with a view to setting aside the decision for deportation which was rendered by our Officer.”[10] Immigration officials wondered whether they could deport Rebecca Grizzle for being a public charge even if an organization paid her hospital expenses. Four days later, E.L. Newcombe, Deputy Minister of Justice responded by indicating that an order to deport Rebecca as a public charge “could be legally executed if an organization interested in this party should pay her hospital expenses. I am of [the] opinion that such a step would not affect the right established to deport within the authority [of the law]…”[11]

With the assistance of the private organization, Grizzle could have paid her medical expenses. Yet, Canadian officials sought no reason that prevented them from deporting her. What ultimately occurred to Grizzle and the private organization interested in her care is unknown. More research is required to find out what happened to her.

It would take another two decades before five women took a Supreme Court of Canada decision in Edwards v Canada (commonly referred to as the “Persons Case”), to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in Great Britain, which at the time served as the highest court of appeal for all Commonwealth countries. On 18 October 1929, Canadian women were declared as persons before the law.

Conclusion

The archival records that I briefly touched on are insightful regarding government bias and lived experiences of gender discrimination, but do not conclude with any information on what happened to either Rebecca Barnett or Rebecca Grizzle. Was Barnett sent to the United States – the home of her now ex-husband Alfred – or did she remain in Canada as a patient of the Hamilton Asylum? Did the unknown organization interested in helping Grizzle pay her hospital bill, eventually preventing her deportation as a public charge? Did the organization pay for her stay at Toronto General Hospital? More research is required to determine what ultimately happened to both Rebeccas. In the case of Rebecca Barnett, Canada and the United States refused to grant her citizenship, forcing her to become a statutory alien. Although she was born and raised in Canada and ultimately returned to reside in her country of birth for several decades, under the law she was no longer considered a Canadian citizen. I cannot help but wonder, what role her identity as an African Canadian woman with a mental illness played in the exchanges between federal and provincial officials? Given the broader context of systemic racism within both government and social structures at the time, it is at least possible, if not plausible, that her identity as an African Canadian woman played a role. The archival records that I consulted did not answer these questions, but did highlight them.

- Monique Benoit, “No. 119 Are Women Persons? The “Persons” Case,” accessed: 15 January 2013, http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/publications/archivist-magazine/015002-2100-e.html#a4.

- Library and Archives Canada (hereafter LAC), Immigration Branch (hereafter IB) fonds, RG 76, vol. 477, file 737470 “Rebecca Barnett, Undesirable (Insane) (Black),” reel C-10412, letter from S.A. Armstrong, Ontario Inspector of Asylums, Prisons, and Public Charities to W.D. Scott, Superintendent of Immigration, 6 November 1907, 2.

- LAC, IB fonds, RG 76, vol. 477, file 737470 “Rebecca Barnett, Undesirable (Insane) (Black),” reel C-10412, letter from Wallace, Acting U.S. Commissioner of Immigration, Montreal to W.D. Scott, Superintendent of Immigration, 12 November 1907, 2.

- LAC, IB fonds, RG 76, vol. 477, file 737470 “Rebecca Barnett, Undesirable (Insane) (Black),” reel C-10412, letter from Wallace, Acting U.S. Commissioner of Immigration, Montreal to W.D. Scott, Superintendent of Immigration, 15 November 1907, 2.

- LAC, IB fonds, RG 76, vol. 477, file 737470 “Rebecca Barnett, Undesirable (Insane) (Black),” reel C-10412, letter from F.H. Larned, Acting U.S. Commissioner-General of Immigration to Acting U.S. Commissioner of Immigration, Montreal, 21 November 1907.

- LAC, IB fonds, RG 76, vol. 477, file 737470 “Rebecca Barnett, Undesirable (Insane) (Black),” reel C-10412, letter from S.A. Armstrong, Ontario Inspector of Asylums, Prisons, and Public Charities to W.D. Scott, Superintendent of Immigration, 4 February 1908.

- LAC, IB fonds, RG 76, vol. 477, file 737470 “Rebecca Barnett, Undesirable (Insane) (Black),” reel C-10412, letter from S.A. Armstrong, Ontario Inspector of Asylums, Prisons, and Public Charities to W.D. Scott, Superintendent of Immigration, 4 February 1908, 2.

- LAC, IB fonds, RG 76, vol. 477, file 737470 “Rebecca Barnett, Undesirable (Insane) (Black),” reel C-10412, letter from S.A. Armstrong, Ontario Inspector of Asylums, Prisons, and Public Charities to W.D. Scott, Superintendent of Immigration, 4 February 1908, 4-5.

- LAC, IB fonds, RG 76, vol. 477, file 737470 “Rebecca Barnett, Undesirable (Insane) (Black),” reel C-10412, letter from W. Stuart Edwards, Acting Deputy Minister of Justice to Superintendent of Immigration, 31 January 1916.

- LAC, Department of Justice (hereafter DJ) fonds, RG 13, vol. 2178, file 1923-1443 “Deportation of Rebecca Grizzle (Coloured) Public Charge in Toronto General Hospital,” reel C-10412, letter from Assistant Deputy Minister of Immigration and Colonization to W. Stuart Edwards, Acting Deputy Minister of Justice, 18 August 1923.

- LAC, DJ fonds, RG 13, vol. 2178, file 1923-1443 “Deportation of Rebecca Grizzle (Coloured) Public Charge in Toronto General Hospital,” reel C-10412, letter from E.L. Newcombe, Deputy Minister of Justice to Assistant Deputy Minister of Immigration and Colonization, 22 August 1923.