by Jan Raska, PhD, Historian

(Updated October 16, 2020)

Introduction

After the Second World War, a growing population and an economy devastated by war were leading reasons for many Dutch immigrants to seek economic opportunity in North America. A total of some 500,000 Dutch nationals left their homeland from the late 1940s to the 1970s. Approximately 185,000 individuals, or 37 percent of the movement, chose to resettle in Canada.[1] The Netherlands experienced a surplus of farmers after the Second World War due to the destruction of its dykes by German forces, unworkable land, and unemployment. Much of the country’s agricultural land was flooded. In an attempt to increase Canada’s rural population, Canadian officials signed their first postwar bilateral immigration agreement with the Dutch government to bring families to Canada. Between 1947 and 1949, close to 16,000 individuals from Dutch farm families resettled in Canada. A majority of these newcomers resided in Ontario, with sizable populations in Quebec, Alberta, Manitoba, and British Columbia. Under the resettlement scheme, 94,000 Dutch immigrants came to Canada between 1947 and 1954. Over 80 percent of these individuals were agriculturalists. Most of these Dutch immigrants chose to resettle on farms in the southern regions of Ontario and Alberta.[2] The success of this resettlement program encouraged Dutch agriculturalists to immigrate to Canada during the 1950s.

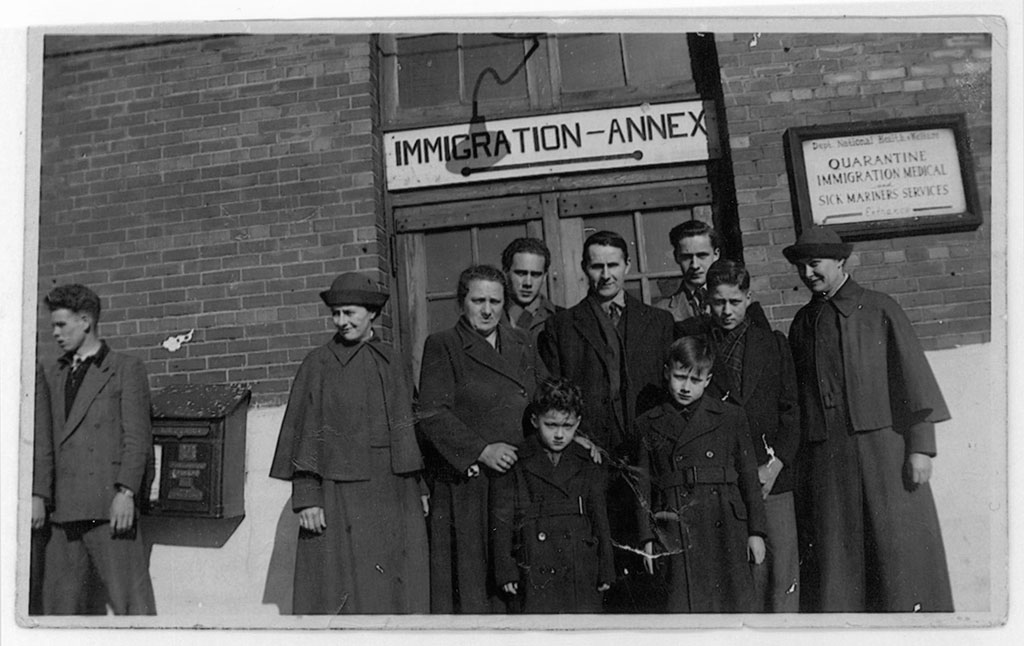

Arrival of Dutch Immigrants at Pier 21

The Canadian and Dutch governments relied heavily on religious organizations to help place immigrants across the country. These organizations chose areas they were most familiar with and believed would bring economic opportunity to Dutch newcomers. Since the 1890s, the two provinces with the largest arrival of immigrants from the Netherlands were Ontario and Alberta. Interest in other provinces slowly increased as well. By the late 1950s, Dutch immigration was comprised mainly of workers and professionals who sought opportunity in urban areas.[3] Historian Donald H. Avery notes that the “low level of re-emigration suggests that most realized their goals. But now it was not the prairie West that attracted most immigrants. Instead, over half of the newcomers gravitated toward the major centres of Ontario, most notably Toronto.”[4]

Before the newcomers disembarked from their ships at Pier 21, railway officials came aboard to hand out name tags listing destination, name of sponsor, name of terminal or transfer station, and the number of the train and the car. The railway ticket was usually paid for in advance. The immigrant then presented the travel voucher at the ticketing counters to be validated. Afterwards, the newcomer would normally telegram his or her new employer to inform them of their expected time of arrival. After having been processed through immigration and customs, Dutch immigrants made their way onboard the train where church representatives walked through the aisles distributing newspapers. Dutch Catholics received Onder Ons, members of the Reformed Church were issued the monthly, Pioneer, while members of the Christian Reformed Church were given the Calvinist Contact.

Individual Experiences of Arrival at Pier 21

A number of personal stories from Dutch immigrants who arrived in Canada through Pier 21 can be found in the Museum’s story collection. In March 1952, Ben and Tina Afman arrived at Pier 21 aboard SS Zuiderkruis and were greeted in the large hall by representatives of the Canadian Red Cross who offered the family cookies, milk, and coffee. The local Dutch consul informed the couple that the rubber boots their children were wearing were not warm enough for a Canadian winter. The Afman fammily spent a boring day in Halifax awaiting their evening departure. They wandered the city buying bread, jam, and butter having been informed that the prices aboard the train were higher than in the city.[5]

Sixteen year old Dori van Schagen spent six weeks at Pier 21 when her father’s sponsor backed out of his farm labour contract. Dori notes that she and her father were given a glass of water and a bottle of ketchup as they went to Pier 21’s kitchen for lunch. Neither knew what to do with the items and thought “maybe we had to make our own tomato juice, so we stirred the ketchup into the water.” Dori’s mother could not locate a laundry room and was forced to wash the family’s underwear in the evening and hang it on the heat registers to dry.[6]

Reverend H.J. Spicer welcomed many Dutch families when they disembarked at Pier 21. Spicer remarks that the large halls into which immigrants were shepherded resembled large warehouses: “the halls were huge, certainly bigger than the space at the Wilhelminakade in Rotterdam. Still, one is able to find his way. He ends up in a bare hall and sits down on a hard bench with other immigrants, waiting for his turn to have his papers inspected.”[7] Some Dutch immigrants retained bitter memories of the immigration facilities at Pier 21. Some were held there for days with little freedom of movement, while officials tried to find them a sponsor. Upon arriving in July 1948, Mary De Jong recalls that the bars and cages gave her the impression that Pier 21 was more “like a jail” than an immigration shed. In a similar recollection, Anne Hutten’s father described the immigration facility as fit for “criminals” upon the Hutten family’s arrival in Canada.

Dutch Canadian author Albert VanderMey notes that many individuals “weren’t impressed with the Halifax harbourfront, or with the city itself. They thought it was a rather dismal-looking place. It certainly was nothing like the bustling world port from which they had set sail.” Rimmer Tjalsma, the landing agent for Holland-America Line, found the city so depressing that he looked forward to a “break” – meeting ships in Quebec and Montreal, the two other major ocean ports of entry in Canada. In October 1954, Tjalsma wrote to a friend in Ontario indicating that “Halifax is still dull and drab-looking as ever and I’m hoping for an eventual relocation. Any place is better than this hole. I hope it will be Montreal, or Toronto, so that I can return to civilization. As you know there is nothing doing in Halifax. It’s a first rate place for sailors and people who love fish.”[8]

Dutch immigrants expressed a diverse range of emotions and opinions of their new surroundings at Pier 21 and throughout Halifax. Canadian officials remembered them for their habit of bringing their household goods in huge wooden crates called kists. Pier 21 officials joked that the kists contained everything but the kitchen sink. One day, a Canada Customs officer opened a large crate only to discover a kitchen sink among the other items.[9]

By 1958, emigration from the Netherlands declined significantly as the country’s economy began to recover, due in part to international assistance.[10] Between 1946 and 1968, the Netherlands was the fifth-largest source country for immigrants to Canada. During this period, 167,327 immigrants declared Dutch citizenship upon entering Canada.[11] Dutch immigration was only surpassed by the arrival of immigrants from Britain, Italy, West Germany, and the United States.[12]

Conclusion

In an attempt to increase immigration to its rural areas, the federal government signed its first postwar bilateral immigration agreement with the Dutch government, in order to bring families to Canada. Between 1947 and 1954, 94,000 Dutch immigrants came to Canada under this resettlement scheme. Over 80 percent of these newcomers had an agricultural background. A majority of the Dutch immigrants chose to resettle on farms in the southern regions of Ontario and Alberta. During the 1950s, many Dutch agriculturalists were encouraged to immigrate to Canada due to the success of the resettlement scheme. The Canadian and Dutch governments relied heavily on religious organizations and voluntary service agencies to help place immigrants across the country. These organizations chose areas they were most familiar with and believed would bring economic opportunity to Dutch newcomers. However, many Dutch farmers left their rural surroundings for economic opportunity in Canada’s cities. Between 1946 and 1968, the Netherlands was the fifth largest source country for immigrants to Canada. Some of these individuals and families arrived in Canada at Pier 21. As a result, Dutch immigration is an important part of Pier 21’s postwar history.

Credit: Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 Collection. (DI2013.1531.1)

- G.H. Gerrits, Peoples of the Maritimes: Dutch (Tantallon: Four East Publications, 2000), 35.

- Donald H. Avery, Reluctant Host: Canada’s Response to Immigrant Workers, 1896-1994 (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1995), 200.

- Herman Ganzevoort, “Dutch,” In Encyclopedia of Canada’s Peoples, ed. Paul Robert Magocsi, 435-450 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1999), 441.

- Avery, Reluctant Host, 13.

- Albert VanderMey, To All Our Children: The Story of the Postwar Dutch Immigration to Canada (Jordan Station: Paideia Press, 1983), 129-133.

- Anne van Arragon Hutten, Uprooted: the Story of Dutch Immigrant Children in Canada, 1947-1959 (Kentville: North Mountain Press, 2001), 65.

- VanderMey, To All Our Children, 119.

- VanderMey, To All Our Children, 118-119.

- Canada Employment and Immigration Commission, Public Affairs, Nova Scotia Region, “The Pier 21 Story: Halifax, 1924-1971,” n.d., 9.

- Joseph A. Diening, “Contributions of the Dutch to the Cultural Enrichment of Canada,” Report Presented to the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism (May 1966), 28.

- Canada, Department of Manpower and Immigration, 1968 Immigration Statistics (Ottawa: Queen’s Printer, 1969), 22.

- Freda Hawkins, Canada and Immigration: Public Policy and Public Concern (Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1988), 54.